Nowhere are the contradictions in the English character and its history so apparent than in the dramatic events surrounding Campion's last days, the perfidy and sophistic contortions of his prosecutors contrasting so violently with Campion's saintliness and sublime appeal to Reason.

This is not the place to recount the details of Campion's life; brief summaries may be found at Wikipedia and, more trustworthily, the Society of Jesus website. My main purpose is to recommend Evelyn Waugh's book and feature some other web resources on Campion's life. It is a measure of Waugh's intelligence that he grasps the truth that what the Jesuit martyrs were importing from the Continent into Elizabethan England was in effect a new religion, bearing little relation to what went before, importing it into a land whose rulers had, like so many in the north, chosen to reject the civilisation of the Renaissance embodied in the Catholic counter-reformation. This is apparent in the following quotes from Waugh:

"They were conditions, which, in the natural course, could only produce despair, and it depended upon their individual temperaments whether, in desperation, they had recourse to apostasy or conspiracy. It was the work of the missionaries, and most particularly of Campion, to present by their own example a third supernatural solution. They came with gaiety among a people where hope was dead. The past held only regret, and the future apprehension; they brought with them, besides their priestly dignity and indestructible creed, an entirely new spirit of which Campion is the type: the chivalry of Lepanto and the poetry of La Mancha, light, tender, generous and ardent."

"To the Catholics, too, it meant something new, the restless, uncompromising zeal of the counter-Reformation. The Queen's Government had taken away from them the priest that their fathers had known; the simple, unambitious figure who had pottered about the parish, lived among his flock, christened them and married them and buried them; prayed for their souls and blessed their crops; whose attainments were to sacrifice and absolve and apply a few rule-of-thumb precepts of canon law; whose occasional lapses from virtue were expected and condoned; with whom they squabbled over their tithes, about whom they grumbled and gossiped; whom they consulted on every occasion; who had seemed, a generation back, something inalienable from the soil of England, as much a part of their lives as the succession of the seasons - he had been stolen from them, and in his place the Holy Father was sending them, in their dark hour, men of new light, equipped in every Continental art, armed against every frailty, bringing a new kind of intellect, new knowledge, new holiness. Campion and Persons found themselves travelling in a world that was already tremulous with expectation."

Evidence not only of Waugh's perspicacity, but also of his admirably sinuous and nuanced style. In 1946 Waugh wrote a new preface for the American edition of the book, in which he says the following:

"We [in 1946] have come much nearer to Campion since Simpson’s day [referring to Simpson's 1867 biography of the Saint; see below]. He wrote in the flood-tide of toleration, when Elizabeth’s persecution seemed as remote as Diocletian’s. We know now that his age was a brief truce in the unending war... We have seen the Church driven underground in one country after another. The martyrdom of Father Pro [of the Society of Jesus] in Mexico re-enacted Campion’s. In fragments and whispers we get news of other saints in the prison camps of Eastern and South Eastern Europe, of cruelty and degradation more frightful than anything in Tudor England and of the same pure light shining in the darkness, uncomprehended. The hunted, trapped, murdered priest is amongst us again and the voice of Campion comes to us across the centuries as though he were walking at our side."

For Mexico and Eastern Europe substitute China, Iraq, Pakistan, and the above passage might have been written yesterday. In the book Waugh paints a picture of the road ahead for England at the time of Queen Elizabeth's death in 1603:

[Elizabeth] "... left a new aristocracy, a new religion, a new system of government; the generation was already in its childhood that was to send King Charles to the scaffold; the new rich families who were to introduce the House of Hanover were already in the second stage of their metamorphosis from the freebooters of Edward VI’s reign to the conspirators of 1688 and the sceptical, cultured oligarchs of the eighteenth century. The vast exuberance of the Renaissance had been canalised. England was secure, independent, insular; the course of her history lay plain ahead: competitive nationalism, competitive industrialism, competitive imperialism, the looms and coal mines and counting houses, the joint-stock companies and the cantonments; the power and the weakness of great possessions."

Of course one cannot consider the England of 1603 whilst ignoring the colossus that is William Shakespeare. Shakespeare's Catholic sympathies have by now been well documented, his father having been a prominent Recusant; indeed, the ghost of Campion himself is present in such plays as Twelfth Night, as demonstrated in this article from the Elizabethan Review by C. Richard Desper.

On leaving Rome for his fatal mission to England, Campion and his companions had been blessed by none other than St Philip Neri in person, stopping on the way at the shrine of St Charles Borromeo in Milan. On arriving in England, he penned the Decem rationes or Ten Reasons Proposed to his Adversaries for Disputation, prefaced by what later came to be known as Campion's brag. Intended as a demonstration of the Truth of the Catholic religion, it is available in its entirety (in Latin and English) at Project Gutenberg.

On his arrest, he was committed to the Tower of London and questioned in the presence of Queen Elizabeth, who asked him if he acknowledged her to be the true Queen of England. He replied she was, and she offered him wealth and dignities, but on condition of rejecting his Catholic faith, which he refused to accept. He was kept a long time in prison and repeatedly tortured. His adversaries summoned him to four public conferences where he was ordered to dispute with Anglican clergy despite his lamentable physical state. The nature of these disputations may be gleaned from the following exchange between Campion and Fulke, an Anglican scholar:

Campion: "If you dare, let me show you Augustine and Chrysostom. If you dare."

Fulke: "Whatever you can bring, I have answered already in writing against others of your side. And yet if you think you can add anything, put it in writing and I will answer it."

Campion: "Provide me with ink and paper and I will write."

Fulke: "I am not to provide you ink and paper."

Campion: "I mean, procure me that I may have liberty to write."

Fulke: "I know not for what cause you are restrained of that liberty, and therefore I will not take upon me to procure it."

Campion: "Sue to the Queen that I may have liberty to oppose. I have been now thrice opposed. It is reason that I should oppose once."

Fulke: "I will not become a suitor for you."

Campion was brought to trial, along with several other priests, for treason, the usual charge brought against Catholic priests. Though there was no evidence that Campion, or those tried with him, had planned or supported any violence against Elizabeth, the charge was rammed through with false witnesses. At his sentencing, he rose and addressed the court and jury:

“In condemning us you condemn all your own ancestors - all the ancient priests, bishops and kings - all that was once the glory of England, the island of saints, and the most devoted child of the See of Peter. For what have we taught, however you may qualify it with the odious name of treason, that they did not uniformly teach? To be condemned with these lights… by their degenerate descendants, is both gladness and glory to us. God lives; posterity will live; their judgement is not so liable to corruption as that of those who are now going to sentence us to death.”

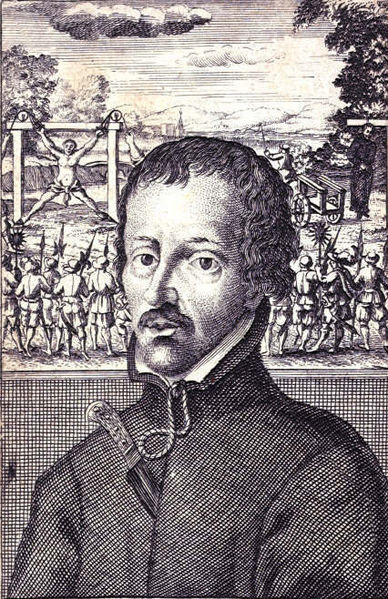

On 1st December 1581 Edmund Campion was dragged through the streets of London to be executed at Tyburn by the contemporary method of hanging, drawing and quartering. This involved being stripped of one's clothing, taken to the scaffold and hanged for a short period, but only to cause strangulation and near-death; then being cut down, disembowelled, and normally emasculated. Those still conscious at this point would have seen their entrails burnt or boiled before them, before their heart was removed. The body was then decapitated, signalling an unquestionable death, and quartered (chopped into four pieces). Each dismembered piece of the body was later displayed publicly.

On 1st December 1581 Edmund Campion was dragged through the streets of London to be executed at Tyburn by the contemporary method of hanging, drawing and quartering. This involved being stripped of one's clothing, taken to the scaffold and hanged for a short period, but only to cause strangulation and near-death; then being cut down, disembowelled, and normally emasculated. Those still conscious at this point would have seen their entrails burnt or boiled before them, before their heart was removed. The body was then decapitated, signalling an unquestionable death, and quartered (chopped into four pieces). Each dismembered piece of the body was later displayed publicly.Evelyn Waugh: "Campion stands out from even his most gallant and chivalrous contemporaries, from Philip Sidney and Don John of Austria, not... by finer human temper, but by the supernatural grace that was in him. That the gentle scholar, trained all his life for the pulpit and the lecture room, was able at the word of command to step straight into a world of violence, and acquit himself nobly; that the man, capable of the strenuous heroism of that last year and a half, was able, without any complaint, to pursue the somber routine of the pedagogue and contemplate without impatience a lifetime so employed - there lies the mystery which sets Campion’s triumph apart from the ordinary achievements of human strength."

Saint Edmund Campion was beatified by Pope Leo XIII in 1886, and canonised in 1970 by Pope Paul VI as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. His feast day is celebrated on 1st December, the day of his martyrdom.

Fully available on Google Books: Richard Simpson's 1867 Edmund Campion, A Biography, and John Morris's 1905 Lives of the English Martyrs.

No comments:

Post a Comment